The Shift Project is a French think tank advocating the shift to a post-carbon economy. As a non-profit organisation committed to serving the general interest through scientific objectivity, we are dedicated to informing and influencing the debate on energy transition in Europe.

INFORM

- We set up working groups on the most sensitive and decisive issues of the transition to a post-carbon economy;

- We produce robust and quantified statements on key aspects of the transition;

- We bring forward innovative proposals, and we pay particular attention to appropriately-scaled solutions.

INFLUENCE

- We launch lobbying campaigns targeting political and economic decision-makers to promote the recommendations made by our working groups;

- We host events designed to encourage discussion among the different stakeholders concerned with climate and energy issues;

- We build partnerships with both professional organisations and academic players.

The Shift Project (TSP) is supported by economic leaders that consider the energy transition as their strategic priority. Since our foundation in 2010, we have signicantly impacted national and European policy-making with regard to the climate and energy issues.

Context

The end of a model

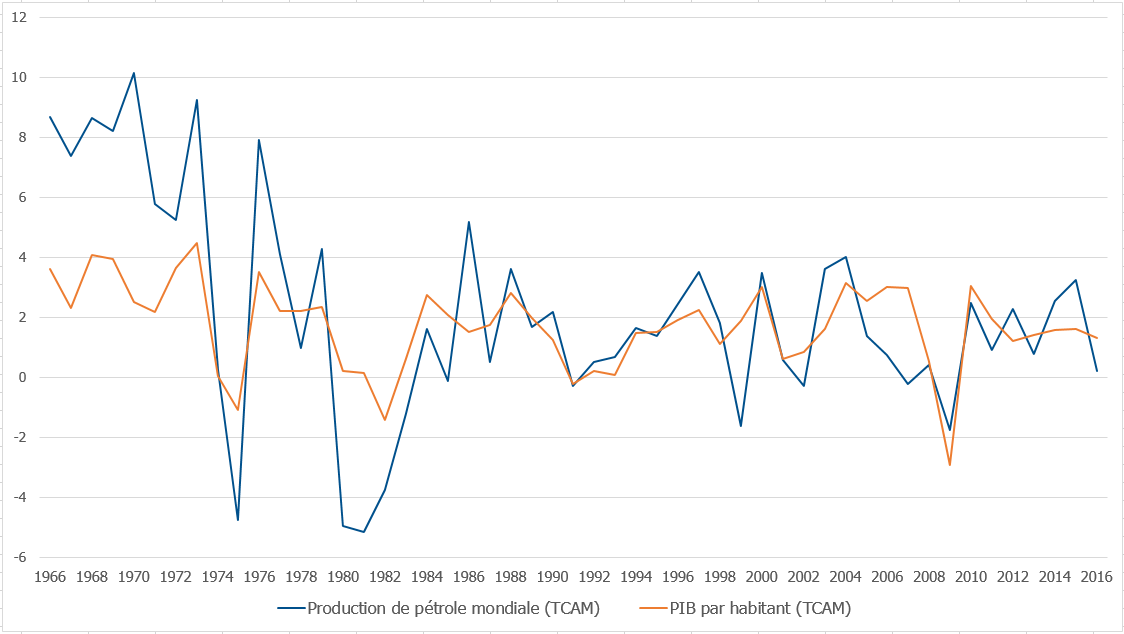

Having been founded for two centuries on making increasing use of resources once thought to be inexhaustible (as can be seen from the bases of classical economics), our economy is now repeatedly coming up against the physical limits of our planet. Until now, we have benefited from energy –essentially carbon-based energy– that was increasingly abundant and becoming cheaper and cheaper in real terms, which enabled continual growth in human productivity. The deep-rooted dependency of GDP on energy in general, and oil in particular, emerges unmistakably when we look at the trends in oil and GDP since 1965.

Blue line: trend in the physical production of oil since 1968 (3-year average).

Orange line: trend in average GDP per head of population worldwide (3-year average).

Sources: World Bank (GDP) and BP (oil production).

The twin constraints of energy and climate change are raising question marks over the very foundations of our industrial societies, since they imply a de-correlation between the feeling of prosperity and the level of physical flows. But reducing the dependency of what we do on flows of materials and energy is becoming a strategic, financial, ecological and social necessity.

This profound change, which is driving one of the biggest challenges of the century, deserves our commitment and effort to bring together as much human energy, will and intelligence as possible in order to prepare for this shift at the earliest-possible stage while identifying all its opportunities. We must anticipate the future and not be hostage to it, since doing nothing will unfortunately result in human drama and suffering more surely than failing to make any effort at all.

The Shift Project is bound up with this vision, and is fully committed not only to understanding the challenges involved, but more importantly to helping us all to succeed in meeting them. TSP is a proactive source of proposals, and contributes to sharing solutions, developing resources, identifying the step changes required and marking out the pathways that will lead us to new models for growth.

The carbon issue

The carbon concept refers to two realities: 80% of the energy consumed in the world comes from fossil fuels, and CO2 accounts for the great majority of our greenhouse gas emissions. We therefore face a double constraint: on the upstream side, the constraint is our stock of energy, and on the downstream side, it is the result of the combustion process used to release that energy that is the root cause of climate change.

Our limited stock of energy will inevitably confront us with a peak of availability, followed by a decline in fossil fuel production, but this geological constraint should not be seen as the only compelling reason for action. The climate-change challenge makes it essential that we reach peak production at an earlier point than that imposed solely by geology, especially in the case of coal. This risks imposing a very significant and unprecedented impact on the primary factor of production that drives our economies.

The energetic constraint

Mathematics allows us to state with certainty that for every resource whose extractable stock is finite, annual extraction of this resource begins at zero, climbs to a maximum and then decreases over time. This conclusion does not apply solely to oil: it is true for all fossil fuels and all minerals (for example, it is highly possible that gold and silver ore have already moved beyond peak production). In the case of oil (1/3 of global energy), those experts closest to the subject estimate that ‘peak oil’ will occur between 2010 and 2020, with ‘peak gas’ (1/5 of global energy) following around 2025. The nature of the peak (whether a distinct spike or a long plateau) and the subsequent speed of decline are subjects of great discussion between experts. Estimates for ‘peak coal’ vary from 2030 to 2100.

Given the importance of energy to the economy, and therefore to society, the implications raised by the occurrence of these peaks are major, and the need to anticipate them is becoming more vital than ever. Unfortunately, the majority of decision-makers in economics and politics do not yet seem to have grasped the importance of the issue.

Climate change

If we are to ensure that global warming does not exceed the limits considered as manageable by a global population of between 8 and 10 billion people (i.e. a temperature rise of 2°C compared with the preindustrial level), we must stabilise the atmospheric concentration of CO2 at around 400 ppm (it has already exceeded 390 ppm). To achieve this, we must begin to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, and reduce them by a factor of between 2 and 3 (depending on whether the comparison is with 1990 or 2010) by 2050.

In practice, this will mean extracting only the oil and gas already discovered, limiting the use of coal to installations with carbon capture and storage facilities within well before 2030, and releasing no more emissions after 2050. As a result of the 2009 Copenhagen Accord, most of the world’s leading countries have committed themselves to GHG reduction targets: 20-30% for Europe by 2020, 30% for the USA by 2025, and looking further forward, most western countries have referred to reducing their emissions by a factor of 4 or 5 by 2050. China has agreed to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by 40% by 2020 .

But when it comes to putting these intentions into practice, the reality does not always live up to the intention. Those public-sector and private-sector actors truly committed to the ‘carbon free’ route remain too few in number to constitute a real lever for change.

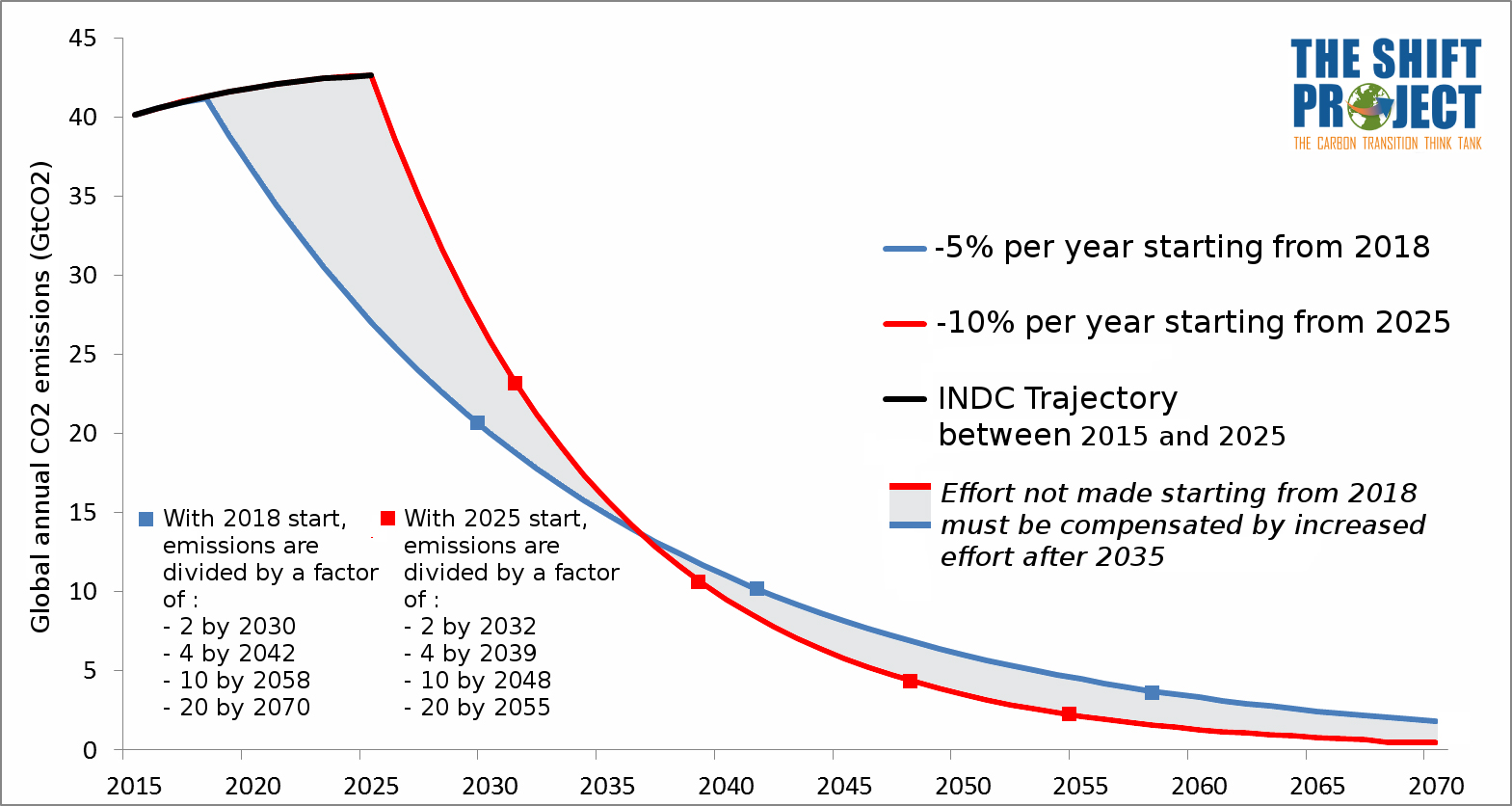

2°C compatible GHG emissions trajectories

[Carbon budget : IPCC ; INDCs : Paris Agreement]

Creation of The Shift Project

A window of opportunity

The financial crisis that has gripped the economies of Europe since 2008 has opened up a breathing space in which to consider step change scenarios. Governments have shown themselves capable of injecting several thousands of billions of dollars (between 15% and 25% of global GDP, according to sources) to save the struggling global banking and financial infrastructure, which they believed crucial to their economies.

Since our planet –the source of all the resources that ‘make the machine work’– is even more crucial to the economy, it is now becoming acceptable to envisage step change scenarios of a size at least equivalent to that implemented to save global finance. Repeated crises have created the widespread feeling that the old recipes are working less and less effectively, which in turn is creating a major opportunity to suggest different ways forward.

The Shift Project‘s positioning

The Shift Project wishes to promote a sustainable economy that is neither anti-capitalist in principle nor out of step with scientific fact. Although we share certain characteristics, we do not define ourselves as a scientific body or as a ‘traditional’ environmental NGO. Neither do we represent a particular strand of business.

- The role of the scientific bodies representing the academic world is to identify the contours of the problem to be solved, but their mandate is not despite widely-held confusion– to suggest a solution to the problem they identify and highlight (which will form part of what The Shift Project does).

- Historically the first to have brought the debate into the public arena, the Environmental Non-Governmental Organisations (ENGOs) are often the most active in specific sectors (pesticides, nuclear power, transport, etc.), but rarely study those systemic changes that require a global overview of the possible trade-offs, and especially economic trade-offs. Added to which, they do not in all cases reflect the reality of the science involved, which makes them less influential amongst certain types of decision-makers.

- Some of the industry bodies that defend the interests of particular sectors of the economy are capable of being simultaneously in agreement with the scientific facts and in a position to make constructive economic proposals. But this is not always the case and, generally speaking, they are rarely promoters of an overview on economic reorientation. More specifically, they often have the habit of thinking that traditional economic indicators take precedence over physical approaches –which is not TSP’s point of view. As a result, they are sometimes tempted to repudiate facts whose logical conclusions would impose constraints on the areas of industry they represent.

There is one last point that should be noted: historically, those concerned with climate change and those focused more on energy have more often been opposed in their views than united. A joint approach to the two problems – which is that adopted by TSP – is a very recent development and remains far from complete.

The goal of The Shift Project is to borrow the best from each type of stakeholder to put forward global and constructive overviews, charting the way forward to a carbon free economy – overviews that do not assume a fundamental change in human nature before they can be applied.